Relying on obsolete standards, stifling innovation and a cult-like devotion to consultants and bureaucracy are among the major criticisms leveled at this venerable approach to quality management.

There are plenty of ideas from the 80s that seem painfully outdated today: payphones, cassette tapes, big hair and shoulder pads. But what about Six Sigma? Introduced at Motorola in 1986 by American engineers Bill Smith and Mikel J. Harry, the basic proposition of improving quality by identifying the causes of defects and minimizing process variability has grown into an almost cult-like phenomenon.

Although there is no universal certification body, there are dozens of organizations that offer training and accreditation for Six Sigma experts, including the American Society for Quality, The Chartered Quality Institute and more than fifty universities worldwide. Then there are the consultants and advisory services, from independent specialists on Upwork to industry titans like Bain and Company.

The benefits of Six Sigma tend to be framed in startling figures: billions of dollars in cost reductions supposedly achieved through double-digit gains in production efficiency. And yet, for a management philosophy so focused on statistics, independently verifiable evidence for Six Sigma’s effectiveness seems sorely lacking. What we have instead is mostly anecdotal and, as it’s been observed: the plural of anecdote is not data.

Given the rise of Industry 4.0 and resulting changes in the landscape of manufacturing, it’s worth asking whether Six Sigma’s principles and practices are still relevant today.

Six Sigma in 100 Words

Six Sigma refers to the fraction of a normal distribution curve that lies within six standard deviations of the mean. This represents the target defect rate for a manufacturing process, which works out to 3.4 defects per million opportunities (DPMO). This target is achieved through a combination of various tools and methodologies, such as DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve and Control) for existing processes and DMADV (Define, Measure, Analyze, Design, Verify) for new ones. There are also tools that can be found in other quality management systems besides Six Sigma: the 5 Whys, fishbone diagrams, control charts and cost-benefit analyses.

Who Uses Six Sigma?

Although it began at Motorola, Six Sigma quickly spread to many other large American companies, including Johnson & Johnson, Texas Instruments and, perhaps most famously, GE under the leadership of Jack Welch. Welch is often credited with spreading enthusiasm for Six Sigma after implementing it in GE’s manufacturing operations in 1995.

While the list of companies that claim successful Six Sigma implementations seems impressive at first blush, it’s worth noting that industry winners like Amazon and Google are balanced out by losers like Sears and Computer Sciences Corporation. This raises the question of whether Six Sigma advocates are guilty of a kind of survivorship bias. After all, even the originator of Six Sigma—Motorola—still ended up with staggering losses that led to the company splitting.

Nevertheless, Six Sigma companies do share certain features in common. Chief among these is being relatively large in size, with even the most diehard Six Sigma fans admitting that the philosophy is best applied by organizations with more than 500 employees. Of course, they’ll also add a caveat that there are still many Six Sigma tools and techniques that can work for small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Why waste a chance to recruit more acolytes to The Six Sigma Way?

Criticisms of Six Sigma

While there have been numerous complaints about Six Sigma over the past few decades, they can be roughly grouped into three broad categories: Applications, Effectiveness and Innovation. In each case, these critiques boil down to questioning whether Six Sigma is really worth all the trouble involved in implementing it, though they take different perspectives on where the trouble lies.

Applications of Six Sigma

In a book published the year after Jack Welch deployed Six Sigma at GE, quality consultant Philip B. Crosby pointed out that Six Sigma’s 3.4 DPMO standard was woefully inadequate for semiconductor manufacturing. Since semiconductors contain more than a million components, each of which needs to be defect-free for the entire unit to function, 3.4 DPMO simply won’t cut it. That was in 1996, and semiconductors have only gotten more intricate and complex in the decades since.

Many other complex products have entered the market since Six Sigma was first conceived, including those which use semiconductors as essential components. Given the growing complexities of manufacturing, it’s worth considering whether a quality management philosophy that predates the fall of the Soviet Union is still applicable in the age of Industry 4.0.

Six Sigma’s Effectiveness

Given all the enthusiasm for Six Sigma, one might expect that there would be plenty of evidence for its effectiveness as a quality management strategy. As noted above, there are assertions that companies which have deployed Six Sigma have seen hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars in cost savings as a result—but there are several reasons to be skeptical of such claims.

Satya S. Chakravorty, a professor of operations management at Kennesaw State University, and Praveen Gupta, director of quality for the Stephen Gould Corporation, have separately claimed that over 60 percent of corporate Six Sigma initiatives fail. According to Chakravorty, this is typically due to external Six Sigma experts who initially spearhead these projects but leave before they’re completed. Charles Holland (who, it should be noted, advocates for a competing quality management system) has argued that 91 percent of large companies that announced Six Sigma programs have trailed the S&P 500 since doing so.

The trouble is that the success (or indeed criticisms like Holland’s) of Six Sigma projects may suffer from the old informal fallacy of post hoc ergo propter hoc: after this, therefore because of this. As Yasar Jarrar and Andy Neely put it in their 2003 critique: “[A]re we making a true improvement with Six Sigma methods, or just getting skilled at telling stories?”

Does Six Sigma Stifle Innovation?

Another of Holland’s (admittedly biased) criticisms of Six Sigma is that it was narrowly designed to fix existing processes and, as such, allows little room for new ideas. Jarrar and Neely make similar claims, noting that most organizations are neither designed nor led to allow the kind of statistics-driven management that Six Sigma requires. As a result, incorporating Six Sigma into a company’s culture may inhibit innovation, either because its tools and methods are too rigidly applied due to a lack of internal expertise, or because the bureaucracy of Six Sigma forces all projects to conform to its particular format.

Chakravorty’s research has found that Six Sigma programs can end up adding more work—in the form of statistical analysis—to teams that are supposed to be eliminating waste, not squeezing more tasks into their daily routines. To be fair, this is more of a risk for companies that try to use Six Sigma by enlisting the temporary aid of consultants, rather than relying on internal experts or champions. Nevertheless, given the abundance of companies and specialists offering Six Sigma services, the likelihood of this outcome is certainly nonnegligible.

Is Six Sigma Worth It?

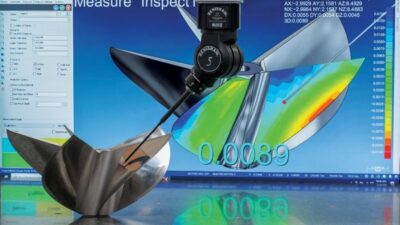

Although it’s obviously different from purchasing a new piece of equipment, such as a coordinate measuring machine (CMM) or a laser scanner, implementing Six Sigma does require a significant capital investment. Whether contracting with external advisors or consultants or building the expertise internally by hiring candidates with Six Sigma certifications or paying for training, Six Sigma doesn’t come cheap.

Is it likely to deliver a sufficient return on investment to justify that upfront cost?

Ultimately, the answer to that question depends on what you’re trying to achieve with Six Sigma and what kind of guarantees its practitioners can offer that isn’t laced in jargon and carefully curated statistics. As Terry Pratchett once wrote: “Always be wary of any helpful item that weighs less than its operating manual.”