What do we really know about Stockton Rush, founder of OceanGate?

The engineer’s relationship with the public is based on trust. The public trusts that we don’t take risks with their lives. If it wasn’t for this trust, nobody would cross a bridge or board an airplane. Such is the faith of the public in engineering—and in modern times, the faith is well deserved. Rare is it that an engineer will risk human life.

Trust is built into the profession. The National Society of Professional Engineers, whose members sign off on drawings of bridges and buildings, states that “Engineers shall hold paramount the safety, health and welfare of the public.” In Canada, many engineers wear the iron ring, after swearing to “not henceforward suffer or pass, or be privy to the passing of, bad workmanship or faulty material,” as written by Rudyard Kipling and first used in 1922.

The public’s trust in engineers is taken for granted.

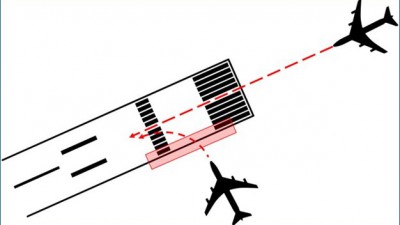

“That engineering side, we just had no idea,” said Christine Dawood, who was widowed after the Titan submersible sank, in an interview in the New York Times. “I mean, you sit in a plane without knowing how the engine works.”

Ms. Dawood also lost her son in the same disaster. It was on Father’s Day, June 18, 2023. The Dawoods had all departed on a support ship from which the Titan was launched. Also on board were veteran deep-sea explorer, Paul-Henri Nargeolet; Stockton Rush, CEO of OceanGate who also piloted the Titan; and aviation tycoon, Hamish Harding.

Who is Stockton Rush?

It may not be fair to blame the late Stockton Rush for the tragedy. He can’t defend himself. To one of the few still in his corner, he was an intrepid explorer not afraid to take risks. Rush was always the first to christen new submersibles and continued to pilot them—is that not brave?

Should he have put others at risk, though? All those, like Ms Dawood, who entrusted Rush with the lives of her son and husband?

While the U.S. Coast Guard continues to conduct its investigation, Rush has already been condemned in the court of public opinion. An avalanche of blame has come down on him. It was an avalanche that Rush invited. He took risks and bragged about it.

“If you just want to be safe, don’t get out of bed. Don’t get in your car. Don’t do anything. At some point, you’re going to take some risk, and it really is a risk-reward question,” he said to CBS News, reported David Pogue in a 2022 interview podcast. “I think I can do this just as safely by breaking the rules.”

With a list of mistakes made, many of them on the record, blaming Rush is like shooting fish in a barrel.

Go, Tigers

Stockton Rush graduated from Princeton University in 1984 with a B.S.E. in mechanical and aerospace engineering (MAE), maintaining a Princeton tradition that goes back to the beginning of the institution. His father, Richard “Tok” Rush, graduated from Princeton. Their predecessor, another Richard Stockton, was one of Princeton’s first graduates in 1748 and went on to sign the Declaration of Independence. His father, Robert Stockton, donated land in Princeton, New Jersey, to draw the college from its original location in Newark. Stockton’s son, Richard “Ben” Rush, would follow in his father’s footsteps with an MAE degree from Princeton in 2011, with a thesis on a robotic arm for a submersible vehicle.

The late Stockton Rush was hardly a model student. According to a fact check by TAPintoPrinceton, as a freshman and still going by his given name, Richard S. Rush was arrested for possession of 25 grams of marijuana. By his senior year, now going as “Tok,” he was charged with drunk driving after skirting a flashing railroad gate and crashing into the Dinky, a shuttle train that connects the Princeton University campus to Princeton Junction.

A “thrill seeker,” Rush became the “youngest jet transport rated pilot in the world” in 1981 at the age of 19. This, according to his bio on the OceanGate website, a claim being repeated everywhere but remains otherwise unsubstantiated.

Rush was thwarted from his dream of becoming a U.S. Air Force pilot because he had 20/25 vision, he says in a 2017 interview by U.K.s Independent. Not enough to need correction in normal life, apparently. Rush is never photographed with glasses, even in 1962, before the advent of contact lenses and laser eye surgery.

Much has been made of Rush’s early start in aviation on OceanGate’s promotional materials and in interviews, which have been picked up without question in most media sites. When Rush was 19, he is said to have achieved the rating of DC-8 Type/Captain at the United Airlines Jet Training Institute, which gave him a license to fly the Douglas DC-8 aircraft. “Rush served as a DC-8 first officer during college summers, flying out of Jeddah, Saudi Arabia for Overseas National Airways under a subcontract from Saudi Arabian Airlines,” according to the OceanGate website. “Over the course of three summers, Rush flew to locations such as Cairo, Damascus, Bombay, London, Zurich, and Khartoum.”

Most of the information about Stockton Rush has come from a single source: Stockton Rush himself, and has spread everywhere, even by normally ultra-responsible sources (New York Times, Wall Street Journal, CNN). Yet, many major achievements claimed by Rush have had little independent corroboration. From a benefit of the doubt, the media heavyweights may have tried, but after finding no evidence to the contrary, accepted Rush’s claim at face value.

Delusions of Grandeur

With the elitism of aristocratic lineage, the Ivy League education and a fondness of risk and adventure may have combined to make Rush seek his place among the elite over those less qualified and less deserving of great success. Here was Elon Musk, not even a degreed engineer, conquering space with SpaceX and land with Tesla. Jeff Bezos had graduated from Princeton with an engineering degree (electrical engineering) 2 years after Rush and had become one of the richest men in the world and taken tourists into space.

After graduating from Princeton, Rush worked at McDonnell Douglas Corporation as a flight test engineer on the F-15 and was stationed at Edwards Air Force Base for testing the F-15’s APG-63 radar system, according to the New York Times. It is not known how long he worked at McDonnell Douglas, but by 1989, he received his MBA from the University of California, Berkeley. He would move to the Seattle area, where he is said to have built his own experimental airplane, but more important to this story, started his exploration of the deep in the Puget Sound,

Rush was to take part in several ventures, including Seattle’s BlueView Technologies, a manufacturer of high frequency sonar systems (acquired by Teledyne) and Remote Control Technology, manufacturer of wireless remote control devices for Exxon/Mobil, Raytheon and Ford, among others. In 2009, he formed OceanGate with Guillermo Söhnlein, an Argentine-born American businessman who left OceanGate in 2013, retaining only a minority share.

Rush may have got the idea to take passengers to the final final frontier, the ocean (space already being explored) after taking a submarine dive off the coast of British Columbia in 2006. Scuba diving since he was 12 but now in his 40s, he may have sought to go deep in relative comfort.

“I wanted to sit in a submarine and watch crabs fighting to the sound of Mozart for two hours,” he tells the Independent.

Also, there was also money to be made in adventure travel, a market segment that had zoomed to $275 billion. People were willing to pay to be first to go into space, why not into the deep? Tickets on a submarine could be sold for a $100,000. Climbing Mt. Everest, which was much more uncomfortable, was being sold for as little as $32,000.

OceanGate began by charging around a $10o,000 for dives to see the Titanic shipwreck in 2018, but after selling out its maiden voyage (according to the Independent), OceanGate was to raise the price of a Titanic expedition to $250,000.

To be continued…