No engineer can stay current on all of the materials that contain PFAS, but a materials database can help.

Countries around the world are seeking to further restrict the use of perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances, encouraging manufacturers to identify cost-effective alternatives that will allow them to offer new and current products. One of their primary tools is materials data management software and add-ons that provide information on legislation, restricted substances, and the use of these substances in particular materials.

One notable project is the development of the PFAS Toolkit for Innovating Replacements (PFASTIR), a library of knowledge about PFAS substitutes. This project is the work of IBM, the University of Pittsburgh, Cornell University, and OntoChem GmbH, a Germany-based company that offers text analysis and data mining products. PFASTIR received a 2022 award from the U.S.’s National Science Foundation to build out and demonstrate the library’s capabilities.

Manufacturers are motivated to take action to find substitutes for PFAS because recent studies and articles have linked them with adverse health effects, including decreased antibody response in adults and children and increased kidney cancer risk in adults. If PFAS are not destroyed through methods like mixing and boiling them with compounds to break them down, they linger for decades in air, soil, and water. In the past three years, academic institutions, corporations, governments, and the general public have gained a greater awareness about the links between PFAS and health problems

Simultaneously, regulatory entities such as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) have encouraged more research on PFAS. Residents around the world have also filed a higher number of lawsuits alleging damage from exposure to PFAS.

In October 2023, government documents revealed that the European Union (EU) intends not to strengthen PFAS regulations in the next few years. Yet the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is considering the first national drinking water standard for six PFAS chemicals. Canada is also taking action to reduce residents’ exposure to PFAS in drinking water. American states from California to Maine are passing new laws to regulate products that contain PFAS. Manufacturers stand to benefit from identifying substitutes for PFAS even if they make the shift years later. Knowing the cost of alternate materials and planning ways to acquire them can help them transition quickly and efficiently.

Why materials databases are effective

PFAS chemicals are water and stain-resistant, a necessity for companies in industries from chip fabrication to aircraft manufacture. In a chip fab facility, PFAS are in valve assemblies and other pipes, tubes, and pumps in semiconductor equipment. PFAS help filter tiny particles from fluids in the process of chip production. In an aircraft manufacturing plant, PFAS are in chemical-resistant tubes, hoses, and fluid seals.

“PFAS can be in anything from cookware to construction materials. It all depends on what a product is made from and how it’s manufactured,” says Roger Barnett, senior product manager for Ansys.

As state, province, and national governments examine PFAS more closely, they tend to add more PFAS to their lists.

“The number of PFAS that are considered harmful are extremely unlikely to ever decrease. Substances usually don’t get taken off the list,” says Barnett.

Stricter regulations can mean that a company will need a special authorization to continue using a certain substance. When the company is not compliant, they can expect fines, product recalls, damage to the brand, and a curtailing of the ability to enter particular markets. In rare cases, a company could even expect line slowdowns or plant shutdowns.

The cost of changing a material is low at the outset, when a company is first contemplating using a material. It rises over time. If the company has to stop using a material at the point of full production, the cost is very high.

“That’s where a materials database is so useful. It can help a company estimate the viability of shifting to a replacement material with no PFAS at different points in the manufacturing cycle, for different products and different outputs,” says Kate Osborne, senior research and development engineer for Ansys.

Using a materials database effectively requires thinking about the database as a way to reduce risk.

When a company is in the conceptual design phase, it can be beneficial for it to estimate cost and feasibility using a generic or typical grade of the material compiled from an assessment of commercially available supplier grades. Later in the design process, the company can update the material to a specific supplier’s grade. This typically requires getting data from the supplier in the form of declarations.

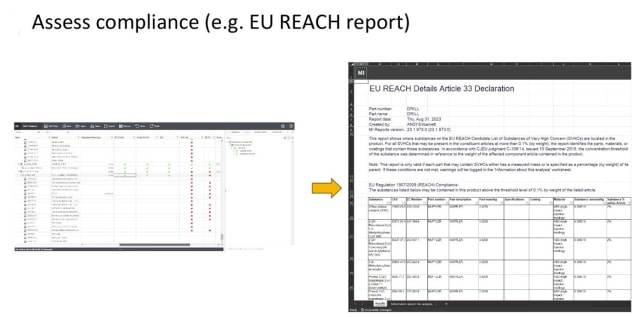

Programs like Ansys’ Granta MI with the Restricted Substances add-on simplify the process. The complete Granta MI dataset with all add-ons has data on 250,000 materials. The program integrates with Computer-Aided Design (CAD), Computer-Aided Engineering (CAE) and Product Lifecycle Management (PLM) software. Granta MI also contains charting and comparison tools. Other measures that manufacturers can take include hiring materials advisors who interview experts and conduct literature reviews on alternate materials. In addition, manufacturers can assist with the development of greener materials and encourage research to accumulate information about PFAS.

How a materials database helps Rolls-Royce

UK-based aircraft engine maker Rolls-Royce wanted to find a way to handle the fact that it had large quantities of legacy data stored in a variety of locations. Absent a systematic approach, the company was duplicating tests. It also saw 40% of all generated test data not reused after initial analysis.

Using Granta MI helped Rolls-Royce improve rates of test data re-use and traceability. This allowed it to maximize the value of critical materials needed for manufacturing. Ultimately, Rolls-Royce realized a savings of $10 million per year through time saved, optimization, and waste reduction.

Barnett says materials databases teach engineers what components contain PFAS and address concerns about supplier data that may be missing.

“There are over 11,000 PFAS substances in the Ansys database. No engineer could be expected to memorize all of the materials that contain them. In addition, this information can change between years. For example, a glass-filled plastic wouldn’t seem to contain PFAS. Yet some do. That’s because PFAS chemicals are sometimes used to lubricate the glass fiber,” says Barnett.

Looking toward the future

When manufacturers stop using materials that contain PFAS, they may have an obligation to look back to bills of materials (BoMs) of past products. Reviewing these documents helps manufacturers, consumers, recycling facilities, and waste management companies understand the risks of handling a manufacturer’s former goods.

The lookback is part of product stewardship, a practice that guarantees product safety and general health for people who come into contact with older goods. A materials database helps manufacturers because it offers a way to “trace back” materials from past products.

A manufacturer who starts and publicizes their effort to identify PFAS in their current and past products now gains a reputational advantage. They also get a jump on new requirements, like providing government agencies with a list of their products that contain intentionally added PFAS. For example, in 2025, Minnesota’s Pollution Control Agency, will require that manufacturers provide the agency with such a list.

Manufacturers who use materials databases can also advance on another front, achieving net zero greenhouse gas emissions. This happens to be one of Rolls-Royce’s goals.

It is possible for companies who look for materials that contain PFAS to note which materials will help them reduce or eliminate carbon emissions in the manufacturing process. A company can then select materials that meet two objectives.

Rolls-Royce’s first step regarding zero emissions involves eliminating emissions from its operations to achieve net zero by 2030. Its second step will involve expanding technologies to product development and testing. The idea is to have all of the company’s new and existing products be designed to achieve net zero.

Barnett says companies with more developed product strategies can set an example for companies that are just beginning to understand PFAS and how restricted substances fall under the broader umbrella of sustainability.

He adds that undoing the excitement of working with materials like Teflon teaches companies to avoid thinking there is a single solution for all products.

“If you’ve got a wonder material that’s banned absolutely everywhere, you don’t have a wonder material. Having information on different materials gives engineers the power to formulate and validate design choices that work with the best replacements. That’s what is going to carry us through the enormous shifts many industries are set to experience,” says Barnett.