Carla Diana delves into how designers can use light, sound and movement to create technology with lifelike capabilities.

In her new book My Robot Gets Me: How Social Design Can Make New Products More Human, author, designer and engineer Carla Diana makes a grand statement: we’re only seeing the tip of the iceberg in terms of smart technology with social design unleashing a new wave of technological advancement. But what exactly is social design? And how will it change everyday technology for the better? From the tiny sleep indicator light on Apple’s MacBook Pro to Alexa and Simon, Diana explains how social design can lead to human interactions with items all around us and help designers embark on a journey to truly “smart” products.

Decoding the Design with Guest Carla Diana

Watch our interview with Author, Designer and Engineer Carla Diana. For full details, read the article below.

My Robot Gets Me: How Social Design Can Make New Products More Human

“You’re not crazy to thank Alexa when she checks the weather. It’s not nuts to name your car Keith (or Fred or Celeste). And it’s perfectly normal to want to repair your Roomba out of loyalty rather than replace it when it breaks,” starts Carla Diana in her latest book, My Robot Gets Me: How Social Design Can Make New Products More Human.

Over the course of the book, Diana explains how social design is all about anticipating the ways in which people will interact with a product in different situations, and then creating the ideal design in terms of these interactions. By examining a product’s core technologies, shape and components, the way the product communicates and the conversation between the user and product, social designers can create a product best suited for various contexts and ecosystems. By thinking about factors such as light, sound and movement, designers can see how an object interacts through a social lens, meaning how it fits in different contexts and exists within the ecosystem of a person’s life.

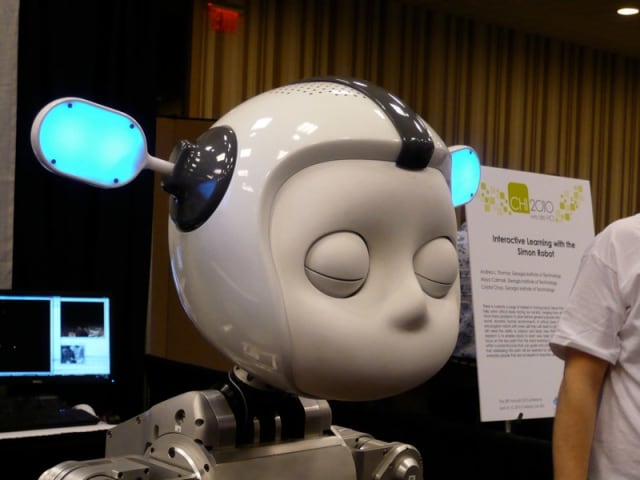

There are many ways to bring light, sound and movement to robotics, Diana explains. For example, the Apple MacBook Pro has the sleep indicator light (which is now a patented feature) that glows and fades at 12 pulses per minute—mimicking the pattern and pacing of human breathing to show that the computer is on and “alive.” Amazon uses sound to create the voice-based command center Amazon Echo, which enables users to do almost anything with the sound of their voice. Movement, which provides the greatest context and non-verbal communication, is an upcoming feature that is being demonstrated through robots such as Moxi, Simon and Curi.

Making New Robots More Human

During her time at the Georgia Institute of Technology, Diana joined efforts with Dr. Andrea Thomaz’s team to create the socially aware robot Simon. Simon is a highly programmed machine that can interact with people and complete simple skills, such as performing household tasks, following directions, tracking motion and recognizing different speakers. Diana worked to lead the creative aspects of designing the five-foot, socially-aware robot’s overall architecture, movement and behavioral characteristics.

Interacting with Simon doesn’t require any knowledge of code, mechanics and button presses. Instead, Simon relies simply on social cues and artificial intelligence for its control and performance. He pleas for forgiveness and expresses his confusion through human gestures such as shrugging or blinking. The two thick antennae, resembling ears, feature two degrees of freedom that can express when he is asleep, awake or in error.

By using speech, gestures and touch, Simon can understand social exchanges and respond appropriately just like you would with another person. According to Diana, “these interactions and emotional exchange can be the difference between a user loving or hating a certain product.”

Similarly, Simon’s “cousin” Curi can let a person know she heard them and is paying attention based on nonverbal, gesture-based communication. She has a similar shell and architectural features, with an expressive round ear and large sympathetic eyes.

“When I interact with Simon or Curi, I know they are machines made of plastic, metal and silicon, yet I still get lost in the sense that I am gazing into the eyes of a living, feeling entity,” says Diana.

A couple of years later, Diana and her team led the creative design work for Moxi. Working with Diligent Robotics, Diana designed Moxi, a clinical robot that helps staff with routine tasks and encourages positive relationships between humans and robots.

While Simon was designed with toddler proportions intended to show users that he was continuously learning, Moxi was required to build trust between hospital patients and staff. To begin work on Moxi, Diana set up workshops where team members acted out the roles of the robot and the nurse using real artifacts in a simulated environment. The idea was to build believable interactions and demonstrate the core conversation between the robot and those around it. Diana set forth using specific scenarios, mock hospital fixtures and props to think about the necessary light, sound and design components to make a more trustworthy robot.

In the end, Moxi was designed with an LED face that visually communicates social cues and shows its intention before moving on to the next task. It relies on a Kinova Jaco arm, and an Adaptive Gripper from Robotiq that helps Moxi pick something up and put it down autonomously. It also has basic capabilities such as navigation and obstacle avoidance.

Using artificial intelligence, image recognition, machine learning, natural language exchanges and robotic control, Moxi can learn new tasks while acknowledging, conversing and engaging with everyone around. These social interactions have a huge impact on how it exudes trust, intelligence and safety. Essentially, the robot’s design features affect the people in the hospital and their state of mind.

Carla Diana: The Author Behind “My Robot Gets Me”

For those of you who don’t know the creative genius behind robots like Simon, Curi and Moxi, Diana is a designer, educator, writer and engineer.

After receiving an MFA in 3D Design from the Cranbrook Academy of Art and a bachelor’s degree in Mechanical Engineering from The Cooper Union, Diana focused intently on social design.

Her work has been featured in countless publications such as Popular Science, Technology Review and The New York Times Sunday Review. She also co-hosts the Robopsych Podcast, a biweekly discussion around design and the psychological impact of human-robot interaction. Many of her projects focus on domestic robots, wearable devices and kitchen appliances.

She has also created the 4D Design program at the Cranbrook Academy of Art, which discusses how to create everyday products that are interactive through projected images, embedded electronics, applied robotics, computer-controlled machining, 3D printing and mixed reality. The two-year MFA program focuses on how objects change with light, sound, motion and time, such as a chandelier that can adjust its position, color and brightness for the right context, or a bin that can navigate through hallways and encourage recycling. Diana has also been a professor at the Parsons School of Design, the Savannah College of Art and Design, and the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Diana created the world’s first children’s book on 3D printing, LEO the Maker Prince, where readers can 3D print any of the characters. By following Carla and the talking, 3D-printing robot LEO on a journey through Brooklyn, children can learn about the basic principles of 3D printing.

Diana’s second book, My Robot Gets Me: How Social Design Can Make New Products More Human, states that the current generation of smart products is not as smart as we think, but rather the beginning stages of what is yet to come. We are only looking at the tip of the iceberg on how everyday products can enhance our lives. Designers will be key in humanizing products through social design principles such as light, sound and movement to evoke human responses in mundane products. Through vision imagery, scenario storyboarding, video prototyping, behavior charting and design production concepts, Diana shares the insight needed for product managers, developers and designers to embark on a journey of truly “smart” products.

My Robot Get Me: How Social Design Can Make New Products More Human releases on March 30, 2021 and is available to pre-order now.